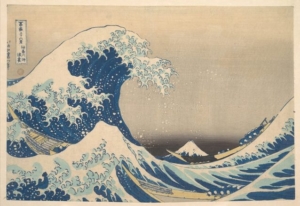

The Wave

There is a beautiful Buddhist analogy of the ocean and the waves. One individual wave could be compared to an ‘I’, an individual ‘I’ -up, existing for a time, and then falling down again once more. And if such a wave would have any feeling, just as it is up at the top, at a crest, in the process of breaking down, hemmed in by other waves all around, would it not be frightened? But if that wave were, in any case, aware that, whether up or down or any other way, it is, in any case, nothing but ocean, and all the other waves around are also nothing but ocean – would there still be a need for any of this commotion? The way out of birth and death.

P31 volume 39 number 2 March 2017 Zen Traces

Image information: 冨嶽三十六景 神奈川沖浪裏

Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), also known as The Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎), ca. 1830–32.

“It will pass”

A student went to his teacher and said, ‘My meditation is horrible! I feel so distracted and my legs ache and I’m always falling asleep. It’s awful!’

‘It will pass,’ the teacher replied matter-of-factly.

A month later, the student returned to his teacher. ‘My meditation is wonderful!’ I feel so aware, so peaceful, so alive!’

‘It will pass,’ the teacher replied matter-of-factly.

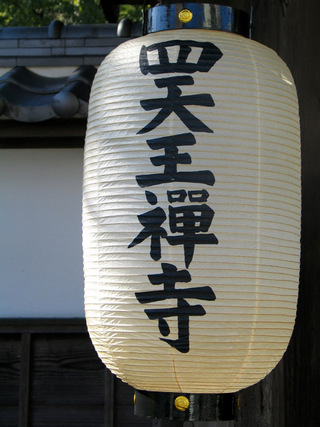

The Lantern

An old Zen master sometimes told this story.

Late one night a blind man was about to go home after visiting a friend.

‘Please,’ he said to his friend, ‘may I take a lantern with me?’

‘Why carry a lantern?’ asked the friend. It won’t do you any good.’

‘No,’ said the blind man, ‘possibly not. But others will see me better and not bump into me.

The friend gave him a lantern.

The blind man went off. But after no more than a few yards, CRACK! Someone walked into him.

The blind man was angry. ‘Why don’t you look out? Don’t you see this lantern?’

‘Why don’t you light the candle?’

From Zen Buddhism

The heart of the sincere believer

Master Sesso said:

‘Though descriptions can be given, what really matters cannot be rendered in words. In front of a Shinto shrine a believer may be seen to pull the straw rope that summons the divinity, then clap his hands three times to indicate he has come worship, and then with folded hands bow deeply in the Presence. All this can be described down to the last detail. The divinity cannot be seen anyway. But what happens in the heart of the sincere believer in the act of bowing, that is the blessing. And that is indescribable.’

From Irmgard Schloegl, The Wisdom of the Zen Masters

The Bottomless Bucket

Stories are part of training in Zen and other Buddhist traditions and in any serious spiritual practice. They help us in realising our true nature for the benefit of others.

Stories are part of training in Zen and other Buddhist traditions and in any serious spiritual practice. They help us in realising our true nature for the benefit of others.

Master Nanrei Yokota tells of ‘the bottomless bucket’. A wealthy man could not find a successor, who would marry his daughter and inherit his fortune. He devised a test for candidates: each would draw water from a well with a bottomless bucket and put it into a small vessel. Almost all gave up at once, thinking that the task was impossible. But one young man resolved to do the best he could even if the bucket could not hold water.

He worked all night. And with each scoop of water from the well, he put the few drops that clinged to the side of the bottomless bucket into the vessel. With steady, persistent application, he filled it up.

Zen training seems to produce no results at first. But little by little, with persistence, it takes effect.

Adapted from Insights into Living: The Sayings of Zen Master Nanrei Yokota

The Tiger and the Strawberry

A man traveling across a field encountered a tiger. He fled, the tiger after him. Coming to a precipice, he caught hold of the root of a wild vine and swung himself down over the edge. The tiger sniffed at him from above. Trembling, the man looked down to where, far below, another tiger was waiting to eat him. Only the vine sustained him.

Two mice, one white and one black, little by little started to gnaw away the vine. The man saw a luscious strawberry near him. Grasping the vine with one hand, he plucked the strawberry with the other. How sweet it tasted!

Joshu’s Zen

Joshu began the study of Zen when he was sixty years old and continued until he was eighty, when he realized Zen.

He taught from the age of eighty until he was one hundred and twenty.

A student once asked him: “If I haven’t anything in my mind, what shall I do?”

Joshu replied: “Throw it out.”

“But if I haven’t anything, how can I throw it out?” continued the questioner.

“Well,” said Joshu, “then carry it out.”

The Moon Cannot be Stolen

Ryokan, a Zen master, lived the simplest kind of life in a little hut at the foot of a mountain. One evening a thief visited the hut only to discover there was nothing to steal.

Ryokan returned and caught him. “You have come a long way to visit me,” he told the prowler, “and you should not return empty-handed. Please take my clothes as a gift.”

The thief was bewildered. He took the clothes and slunk away.

Ryoken sat naked, watching the moon. “Poor fellow,” he mused, “I wish I could have given him this beautiful moon.”

A Cup of Tea

Nan-in, a Japanese master during the Meiji era (1868-1912), received a university professor who came to inquire about Zen.

Nan-in served tea. He poured his visitor’s cup full, and then kept on pouring.

The professor watched the overflow until he no longer could restrain himself. “It is overfull. No more will go in!”

“Like this cup,” Nan-in said, “you are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?”

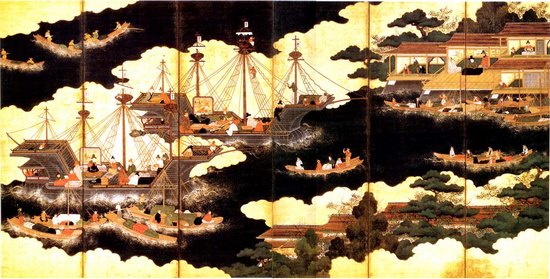

The Two Ships

Nanban ships arriving for trade in Japan. 16th-century painting.

The first T’ang Emperor stood on the bank of the Yangtse river and looked with pardonable pride at the throng of ships that plied up and down its mighty sweep. It was he, the Emperor, who, caring for his people, had brought prosperity nationwide. By his side stood his friend and spiritual guide, a great Zen master.

“See”, said the Emperor, “the busy traffic on the river. Truly the empire is flourishing.” “But I see only two ships on the river”, the Zen master replied. “What are you talking about”, the Emperor wanted to know, “when you can hardly see the water for all the shipping?” “Two ships only”, firmly replied the Zen master, “the ship of profit and the ship of fame.”

The Emperor thought for a while, and then nodded. He undertook sweeping reforms, and set in train the cultural achievement to which the glorious T’ang era attained.

The Buddha’s Fingers

Buddha Hand Detail, Sonnenberg Garden and Mansion State Historic Park, NY

A Buddhist nun in Japan, who by her strong character, far-sightedness and sympathetic persuasion had a great influence in her community where she lived, was asked how she came to give her life to Buddhism.

She said that she had lost her parents when a small child, and had been brought up by her aunt, a nun in charge of a temple. The aunt was very busy also with charitable work, and could not give the child as much time as she would have liked. She took the little girl into the shrine room and they stood before the Buddha image, which showed him seated with the hands joined in the position called Meditation on the Dharma-world. The right hand is laid on the left one with the thumbs joining to form a rough circle.

She presented the child to the Buddha and asked him to watch over her. When they were outside the aunt said: “If you feel you have done something wrong which would make the Buddha angry, at once try to do something good to show your repentance; run and help someone or do some cleaning or tidying up and then go and look at the Buddha. If he is angry with you, his fingers will be in the shape of a triangle. If he has forgiven you, they will be round as they are now.”

This made a big impression. “I can remember many times rushing to the shrine room after hastily sweeping the garden for a few minutes, hardly daring to look at the Buddha’s fingers. I can’t tell you the relief when I saw they were in circles and I knew I was forgiven.”

At this point one of her listeners demurred, arguing, “I don’t approve of using this sort of superstitious falsehood to control the actions of children. They only react against it all when they find out they have been deceived. Didn’t you yourself have a reaction of anger and scepticism when you found out that the fingers of the Buddha never move at all?”

The nun replied, “Oh, it wasn’t a falsehood. My aunt would never have told a falsehood. When I found out that the Buddha never does move his fingers, I realised that the Buddha always forgives. Even at the moment of weakness or sin, the Buddha forgives. He is never angry. And it made me feel that I didn’t want to cause the Buddha to forgive and forgive; I wanted to live so that he would not have to forgive. It was a great help in some crises of temptation and fear. That’s what my aunt wanted me to understand.”

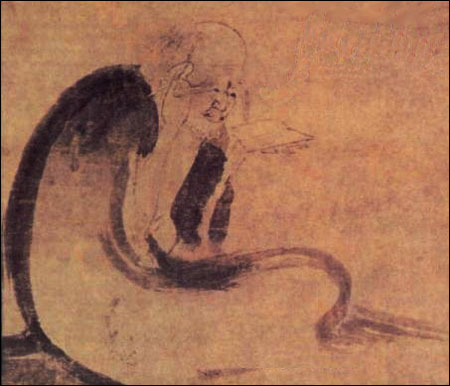

Two Monks

9th century fresco from the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves near Turfan, Xinjiang, China

Two monks on a pilgrimage came to the ford of a river. There they saw a girl dressed in all her finery and obviously not knowing what to do because the river was high and she did not want her clothes spoilt. Without more ado one of the monks took her on his back, carried her across and put her down on dry land. Then the monks continued on their way. But the other monk started complaining: “Surely it is not right to touch a woman! It is against the commandments to have close contact with women! How can you go against the rule for monks?” and so on in a steady stream. The monk who had carried the girl walked along silently, but finally he remarked: “I set her down by the river, but you are still carrying her.”

The Wine Pot

by Trevor Leggett

The final word of Mahayana Buddhism, as expressed in the Flower Garland Sutra of China, is that Samsara, this world of Suffering, is Nirvana, and the passions are enlightenment, bodhi. It is only illusion that causes us to see differences between them. “Samsara is Nirvana, the passions are enlightenment”. This formula has sometimes been taken as a sort of slogan, in isolation from the spirituality of the rest of the Sutra, like the remark of St Paul, “To the pure, all things are pure”.

Two men trained under the same teacher. One became a monk and eventually the head of a monastery. The other also set himself up as a Buddhist teacher. He began preaching the slogan that the passions were enlightenment and enlightenment is the passions. He himself drank heavily and lived licentiously.

One day he came to visit his old fellow trainee, the Zen master. The latter had heard about the conduct of the “teacher”, and when the visitor was ushered into his presence, told him that no-one who is slave to the passions can claim to see them as enlightenment, and that such teaching is of no use to the people.

The teacher indignantly asked why not? The Zen Master merely said that although he did not drink himself, he kept some wine for visitors. Recently they had been given a very rare wine – would he like to taste it?

“Why, yes, yes!”

The Zen Master went out to give instructions to his attendant; as he came back into the room he turned his head and called back, “Absolutely clean, mind!”

When the wine came, the guest could smell the delicious fragrance of it. But to his amazement, it was served to him on what would correspond in the West to an old chipped chamber-pot,

“What’s this?” he cried.

“Oh, don’t mind that. It’s absolutely clean, I assure you – absolutely. What does it matter what the wine is served in? It’s a very rare wine, they say.”

The guest tried to drink but found he could not. He put the chamber-pot down and said, “Why are you doing this?”

The Zen Master replied, “This vessel has been specially made absolutely clean and the wine is a choice one. But you cannot drink it because of the form of the vessel. Now you are serving the wine of the Garland Sutra in the vessel of your life, which may or may not be absolutely pure, but in any case is a form associated with filth. The people will not be able to accept a teaching presented like that.”

The guest changed his way of life.

Encounters

by Trevor Leggett

The temple had a good number of rare manuscripts, and the librarian, who was a good scholar, catalogued them efficiently, and arranged for their publication. Scholars came to consult him from distant centres of learning, and the temple and its librarian became famous.

One day a visitor was congratulating the librarian on his great contribution to learning, and the latter looked out of he window and pointed to an old man sweeping up the leaves in the garden. “People sometimes forget that the library and the whole temple is supported on humble work like that”, he remarked. “in their own way, he and others like him make a great contribution.”

The visitor was impressed and when he said farewell to the abbot he mentioned the incident. “When I saw that humble man sweeping up the leaves,” he said, “I realised the unit of the temple for the first time.”

“Oh, he’s not exactly humble”, answered the abbot. “He’s thinking that although the librarian is so famous and he himself is unknown outside this temple, still when the spiritual accounts are finally made up, it will be the simple gardener who is acclaimed and the arrogant librarian who is humiliated. And in the meantime he gives the assistant gardener hell!

“Both these two have some way to go before they realise that becoming famous as a librarian, and sweeping leaves in the garden, are exactly the same thing, They are occasions for spiritual practice and ultimately spiritual inspiration and illumination. The outward form of the occasion has no importance at all.”

The Diligent Trainee

by Venerable Myokyo-ni

A young layman was training in a Zen temple. He was very diligent, and on hearing that it was one of the virtues of training to secretly get up early and do as many chores as possible, he made it his habit to do so. This went well for a while, and then slowly a change began to come over him. He got up still earlier, and while zealously sweeping and cleaning, resentment stole into his heart. He had harsh thoughts about the lazy-bags still sleeping, waiting for the morning bell to wake them rather than following his example. He worked still harder, with glowering face, depising the others, sweeping as if he was sweeping out demons. The Master, who had been watching him, took him aside and said, ‘It is true that such work is part of the training, but you see for yourself that if done for one’s own sake, for furthering one’s own practice, however good the intention, it turns wrong. Your mind is on you, not on the Buddha. But when you take the Buddha-broom to sweep the Buddha-floor, or the Buddha-rag to wipe the Buddha-table, when the Buddha-hands wash the Buddha-cup, then your Buddha-heart will have joy and contentment and hum a Buddha-song while you work. This is the true practice.’

In a much smaller way, I remember in the early days of my training, when I went for the early morning interviews and occasionally in summer found the monastery gate still closed, I felt a wave of righteous indignation; ‘they ought to be up, it’s their duty, their training; when I can be up, why not they’ and so on. And all that though I knew that ‘they’ had had a specially hard day yesterday.

Later on, I knew that after a really grueling day the monks are allowed to oversleep. And occasionally the monk whose task it is to wake up the monastery, does oversleep; he then has to go to the head-monk and the Master to apologize, and gets scolded. And so, when once in a blue moon I did find the gates closed, a real happiness welled up in me – oh bless them, those poor things, for once they have a bit more sleep, may they go on sleeping for a long time, and I hope the bell-monk will be let off lightly!

A Zen proverb: When we sleep under the same old patchwork-quilt, we all know where the holes are.